BY CHRISLANDE DORCILUS

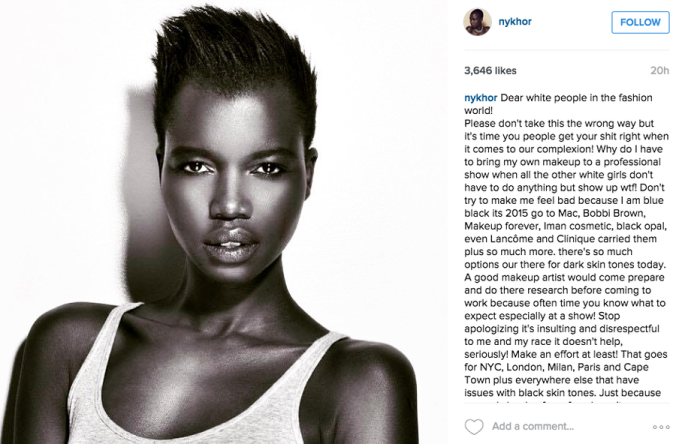

Nykhor Paul, a Congolese model and humanitarian, gave the fashion world a stern talking-to over the weekend. She shamed predominantly white fashion houses and makeup artists for one of the more micro-aggressive racist practices common behind the scenes of fashion: not having makeup or hair styling tools that fit black and brown models.

This isn’t the first time that a black model has spoken out about not being fully equipped or supported to do their job. Supermodel Jourdan Dunn has also tweeted comments about how untrained behind the scene staff at fashion shows seem to be when it comes to black skin and hair.

This incident has me dwelling on the nuanced ways that racism affects black women–specially at work. Let’s take modeling as the ultimate example of gendered and racialized labor: women are more likely to get fame and fortune doing it—one of the few jobs where women can make more than men at all levels of their career. Modeling is also a predominantly white industry.

Nykhor, Jourdan, and other black models make up a very small portion of those being booked in the industry–about 6.8% according to Naomi Campbell. In 2013 this prompted former supermodel Bethann Hardison to pen three letters calling out designers by name for their lack of diversity. Season after season the number of black models has been dwindling. Many in the fashion industry had a hard time pinpointing the problem. The publicist blamed the designer who blamed the casting director who blamed the magazine editors and even still today the buck gets passed around so much that I can’t help but find Hardison’s letter very much relevant. She called it what it was and always will be, “a racist act.”

This form of racism, like all forms of racism, does not cease to function once integration happens. The models that have managed to make it past the policing reality of what it means to be both beautiful and black according to white supremacy, find themselves dealing with another issue: how to be as beautiful as their peers (essentially as good) without the same scaffolding of support available to them.

Imagine getting an office job where everyone had great assistants except for the black coworkers that got sidelined with the incoming interns every quarter. That would be ridiculous wouldn’t it? There’s the hardship of getting the modeling gig–as Nykhor points out black models are few in the fashion industry and then faced with more obstacles of maintaining a gig once booked.

Just as black women in other professional environments have experienced: whether we were ill equipped for specific tasks by an ignorant supervisor, or racist school system. It’s being told to wait for the group and finding that they’d already left–something that’s happened to be throughout my experiences as a black woman, worker, and scholar. The abandonment of both my needs and support by my non-black peers. It’s all akin to the same feeling of having to represent a group, company, project that never believed in you in the first place. Nykhor cannot do the job of modeling without the art of makeup. It’s not fair to her to compete in an environment that is out to make her look “ratchet.” A model with makeup that doesn’t match her skin tone looks idiotic. The long arm of eurocentric beauty standards are accidentally making you look idiotic on purpose. It’s complicated.

Even to those of us that aren’t models and whom are feminist, makeup holds great currency. There are feminist pockets of the internet where talking about contouring and brow pencils is all the rage. Making the self is liberating. Making the self in images that make us feel confident and human is even more liberating. When your job is to represent what it means to be a woman and what it means to be human, finding out that you can’t because of a system that goes out of it’s way to erase your subjectivity and your human needs must be infinitely demoralizing.

At this point, it’s not the makeup companies per se. The higher end brands know that customers of all colors participate in societies impossibly blemish free beauty standards. Nykhor names them in her post – Mac, Makeup Forever, Iman Cosmetics, Covergirl, Black Opal – are all companies that cater to the diversity of black skin, all to varying degrees. Don’t applaud the make up industry yet: there are brands like Neutrogena, Physicians Formula, and Almay which, through their actions say, “Black women need not apply.” Racism is a complicated game of economics. And it’s even more in the world where we are told that those of us who are most successful are the ones that can sell a self. Rants like Nykhors ask us to think about how black women have to compete in the world of work and self composing. The quagmire of fighting beauty standards in a world where we can’t even have any.